San Serriffe’s connection to the tiny mountain village of Topolò/Topolove, near the Italian–Slovenian border, exists in the presence of the visual designer and researcher Francesca Lucchitta, who has been a yearly participant in the activities of the Topolò-based Robida Collective since 2016, and a part of our team at the bookstore since 2020. Together with the baker and artist Sasha van Aalst, she interviewed four members of Robida about the origins of their co-operative project, what it means to work from (and directly with the idea of) the margin, and their shared vision of rural distribution.

Robida’s Dora Ciccone, Elena Rucli, Vida Rucli and Aljaž Škrlep in conversation with Sasha van Aalst and Francesca Lucchitta

At the end of the road that comes up from Clodig/Hlodič there is the village of Topolò/Topolove — a small settlement “but big enough to get lost in”. The road doesn’t go anywhere else. It ends there in the forest, just before the border between Italy and Slovenia. The last possibility for public transport is by train up to Cividale (the nearest town to Topolò). From there either a long walk will follow (around 21 km), a hitch-hike (probably for only part of the road) or someone from the village who is already on their way for errands and can combine a pick up with their travel back up the road.

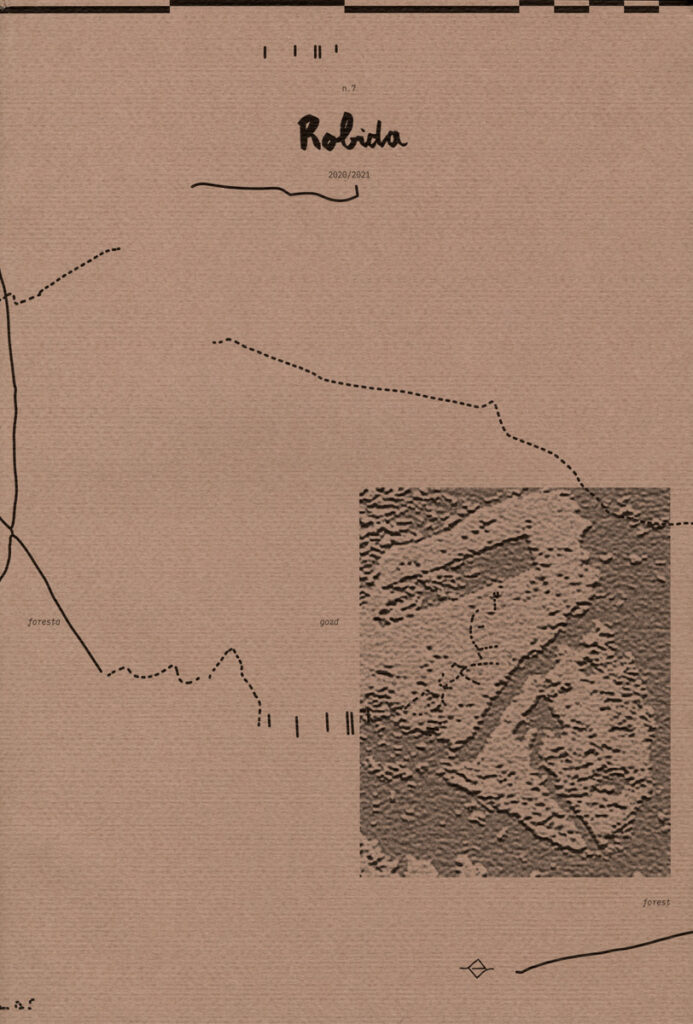

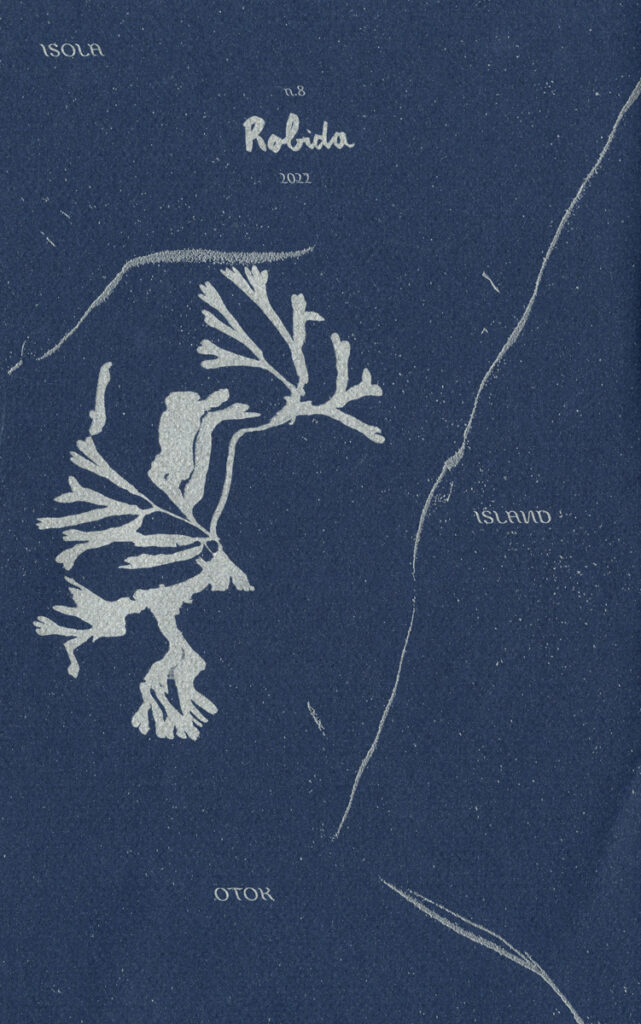

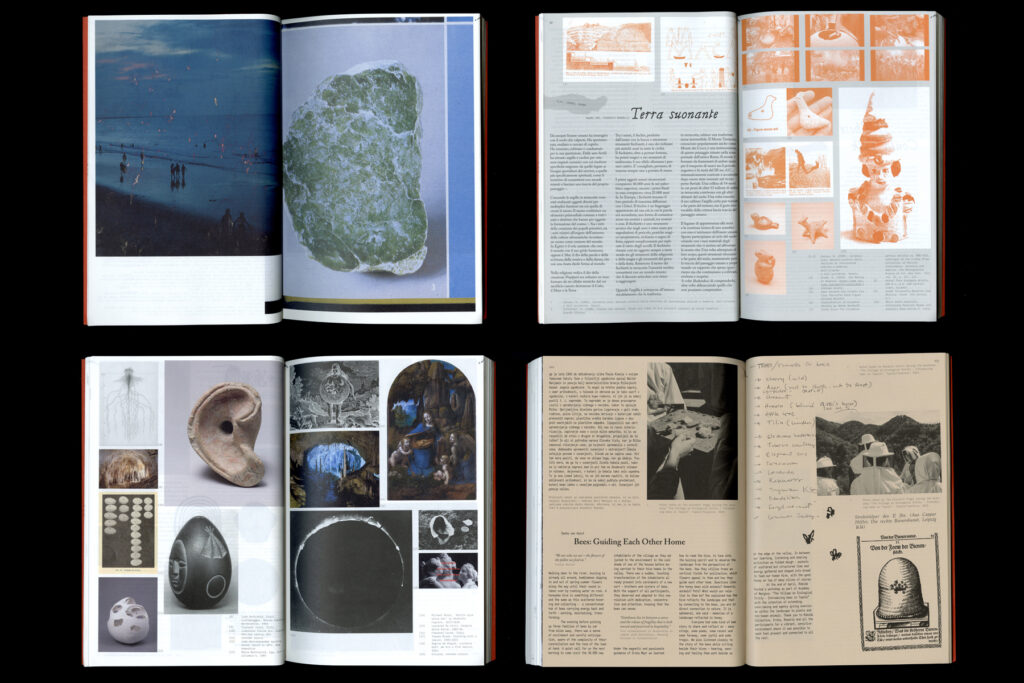

At the moment there are twenty-two people living in Topolò, four of which are part of Robida Collective (Dora Ciccone, Elena Rucli, Vida Rucli, Aljaž Škrlep). The other members live in places nearby and further away (Tanja Marmai in Trieste, Maria Moschioni in Milan, Caterina Roiatti in Seuza, Laura Savina in Rome and Janja Šušnar in Ljubljana). Robida is a curatorial group for long term projects connected to landscape and the place of Topolò. Since 2015 the collective has been curating Robida Magazine, a multilingual cultural magazine published once a year. They also organise residencies, Academy of Margins, which stimulates the encounter between central theories and marginal places, and have been broadcasting through Radio Robida since 2021.

On a Tuesday afternoon Dora was in Cividale to catch us at the train station after work and invited us for a coffee in the city centre. This time we were going to spend around ten days in Topolò to take part in a workshop: Village As Ecological Entity — Introducing Bees In Topolò. Both of us have visited there on multiple occasions. Francesca every summer since 2016, initially for Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove — a yearly art festival that took place in the village from 1994 to 2022 — later she started to collaborate and became involved in different projects. Sasha has visited a couple of times, first after being introduced by friends and now for her own interest in bees, in the collective, and for the possibility of rolling up her sleeves and contributing.

Once the bee workshop ended we took some quiet time and agreed during dinner to meet the following afternoon at Vida and Aljaž’s place. Slowly, from around 5pm, we arrived in the kitchen where Vida was waiting for us. Then Elena and Antonio came. Teo was working in the closest room, and lastly Dora entered from the balcony. Aljaž was in Nova Gorica for work and so he added some reflections later. We sat in Vida and Elena’s grandparents’ old house around their special round table by the woodfire stove, served warm tea to everyone, and after some village talk we started our conversation.

Sasha van Aalst & Francesca Lucchitta: How did Robida come about? Can you explain the context in which things are produced by Robida Collective? Why did you decide to distribute outwards in the first place?

Dora Ciccone: I am from a place closeby and so it was natural, in a way, that I found Topolò. It became a place to feed friendship and to give space to impulsive actions or intentions. It was a place where we were able to make projects and create things by ourselves. It was empowering, inspiring and special to find a place where we were able to grow, in a sense, and be something other than what we were in other contexts.

What comes to mind is when Elena and I learned how to sew with the sewing machine at thirteen [a dialogue unfolds about the pronunciation and conjugation of the word “sew”]. We made bags and sold them to support Postaja/Stazione. We even made a brand and they were embroidered with a paysage of Topolò. In a way it was the first time we produced and distributed something as a small group and we were excited about it. We could have made these bags anywhere else, but we made them here, isolated in Topolò. It was good to have a bubble where we had the possibility to make things without feeling judged and where we could look at things critically only in hindsight. These first projects started a bit naive and spontaneous, something we perhaps lost a bit over time.

SvA & FL: As individuals staying here in Topolò, why did you feel the necessity to do something that reaches others?

Elena Rucli: The answer to this comes in two parts [three actually] that grew simultaneously and gave us the possibility to become the group we are now.

I. The specific way Vida and I grew up in a small village near Topolò, where our mother was living. Together with others she organised an art festival called Stazione di Topolò/Postaja Topolove which connected this isolated village that we knew through our grandparents to the rest of the world. Maybe we never consciously realised that, not only during the summer when the festival happened but also throughout the year, there were always different types of international artists coming through which created a specific environment and a way of thinking that we had around us while growing up.

II. Initially, together as friends, we only created the magazine which was not directly connected to Topolò. That is something you can actually find everywhere: friends that want to do something together.

[Elena realises there is a third part]

III. Then, moving to Topolò gave us the courage to continue with the magazine, to evolve and to initiate new projects on topics specifically related to Topolò and the idea of rurality.

SvA & FL: How and where did the magazine start?

[It takes a familial interaction to get to the following definition]

Vida Rucli: At some point we probably realised that the subjects we chose were unconsciously related to Topolò and so we continued more consciously. What I say now is that Robida is a magazine that deals with themes related to Topolò which are then thrown into the world through an open call. Through the different contributions that come in, we gain a new understanding of what it means to be in Topolò, even if the people contributing are not here or do not know the place itself.

To me another thing is: if in the beginning the magazine was a tool to feed faraway friendships, after, when we moved here, it facilitated our coming into contact with the rest of the world. Along with feeding ourselves with books, internet, etc. to remain in touch and engage with our broader fields of interest, I feel that collaborating and having an exchange with others makes our lives here more meaningful.

FL: It seems to me that the magazine first worked as a way to bind you together. Now there is an association, a place and a different kind of publication that transforms the structure of the collective again and again.

VR: Where does the need to produce something start? I think that for me, personally, producing and distributing not only among friends is us making a sign that we are here. We not only want to be in contact with the world, we also want to say: “Hey, we are here and maybe we are interesting”. The fact that you [Sasha and Francesca, and others living in urban environments] reach out to collaborate makes it worthwhile for us to be here.

And why does this collaboration need to come in the form of printed matter? From the very beginning the main intention of the magazine was to be a relational object. For example, there was a guy that I liked and I proposed to him to make the cover. We got to know each other quite well in the process and, in the end, he told me he was more romantically interested in men than in me [she laughs]. It was perhaps also something we would do as provincial girls reaching out to cool people in the city. Now, it is a bit the same — us still saying: “We are here”. To be honest, it is a nice confirmation that someone in Amsterdam would find it interesting what we do out here. The magazine has become an antidote to our inevitable fear of periphery.

FL: It is nice that the magazine has now become a tool to relate to rurality. If I think about a shop with magazines in a big city, many of these are perhaps also designed, printed and bound in the city itself. Despite the fact that this magazine is created in a very specific environment, it still does well and can sell in an urban environment.

VR: Is it visible that the magazine is a tool for us to foster connections that are essential for us living at the margins? It is good to notice that people in the cities like what we do, but sometimes we wonder if they realise that we really need this engagement and contact in order to be able to live here. I ask myself whether these needs transpire from the magazine?

ER: We actually see that when we go around with the magazine, in addition to an initial interest in the content and the object itself, people most often become more fascinated with our story and the connection the collective has to the village of Topolò.

VR: This is very sad to say, I would never say this in an interview. To me it is a failure of the magazine if people are more interested in our story than the content of the magazine itself.

FL: In terms of making things public and what exactly you make public, the fact of having a website and social media is also a strong influence, of course. Before people get to know the magazine they find your online presence. That’s often the first contact people have with you and spurs a lot of questions about how you live and what you do.

VR: Over time, our Instagram somehow became a professional representation of our collective — even too much, maybe. People get the idea that we are a big institution and they are surprised to hear that we are not able to pay contributors. When you come here everything about your perception changes so much. We are not so professional in the end, but kind and caring people who live together without rigid structures. Relaxed and disciplined! It is important to think about making a digital representation that is aligned with the reality here. We designed and programmed our website with Benjamin Earl and Kirsten Spruit and have been in conversation with them about this, both in Topolò and from a distance.

Of course we always try to execute our projects well and with a lot of attention. They could seem professional but when you come to Topolò and see our internal structure, you perhaps come across Vida and Elena zumzumzumzumzum fighting… Dora tatatatatatata doing ten things at a time. We don’t have an office — the organism that produces tight and neat things is a total mess.

SvA: This mess is also because you are living together.

ER: Yes. Meetings are often postponed because things happen in the village that ask for our attention. Then we have Laura in Rome, for example, who’s like, “Yeah, then I can’t join,” and needs a fixed time. Or there’s Maria in Milano and Janja in Ljubljana who have more structured rhythms too.

FL: Whether or not the perception people have of you coincides with your reality and what it actually looks like to live and work from there all depends on how you communicate.

Everyone: Exactly.

VR: Maybe you can tell us if the Instagram or website reflects us or not, and if not, what we could change a bit so it reflects us a bit more.

ER: [If it doesn’t reflect us] we are fake [collective laughter].

VR: For me it’s also interesting to reflect on the radio as something quite different from the magazine. It is evidently something we do in order to be closer to the broader Robida family that already knows us. It is clearly a tool to discover things we are interested in, something we do just because we want to do it — at the moment, we do not do the radio as “work”. What is different is that the magazine is a clear way of presenting us to unknown people, but if someone who doesn’t know the collective hears our radio, they won’t get much from it because it is random and quite specific to us. I think the reason friends click play is to be with us — we have created a space where we can be together.

[In the summer of 2021, Robida Collective invited Rotterdam-based artist and designer Jack Bardwell to the village to set up an online radio station through a workshop. The radio that started during that week still exists and expands today.]

ER: This is also the way that Robida magazine started. A genuine way of growing things.

FL: These two spaces are try-out spaces, as Dora explained in the beginning. Experimenting — the radio allows you to do this.

[Cat enters and is discussed.]

VR: [Says something in Slovene.]

ER: We live in a village of twenty people and we have a magazine, events and radio programs, and people are surprised and think: Oh, wow. It is good that the magazine exists, but it is just one of the many things that we do. When the magazine started to have a bigger audience, we felt it was important to show its context within its pages.

VR: With this wider reach we added a section to the last magazine [Robida 9: isola otok island], printed on yellow pages, that is not related to the theme of the publication but is about different projects that are happening in Topolò. This section is written by contributors who have spent time in Topolò and is a way to reflect back on projects. When our distribution was hand-to-hand and closer to home we could contextualise in person. When it became more autonomous and the distance farther away, the need arose to add this kind of contextualisation.

SvA & FL: Speaking of contextualisation, can you speak about the way in which you relate to the marginal territory you find yourselves in and its cultures on the shifting borders of two countries?

VR: We experience a double relation to the place where we are. On the one hand it feeds our relations, practices, topics and life. On the other side there is a critical stance we take by not adapting or giving in to what this rural context wants from us in a traditional sense. Adapting would mean having a conservative relation towards the culture we are a part of, which would mean preserving languages, landscapes, traditions etc. without question. Instead, as a point of research we choose to deal with the topics of our minority, or minorities in general, by going out of this usual discourse of preservation, conservation, tradition, memory and heritage, and into collaboration through input from outside. This is always a struggle to achieve.

ER: For me it is both things. There is a heritage we want to preserve, but at the same time we want to speak about things such as rural architecture in a new way.

VR: It is not only interpreting tradition in a different or contemporary way, but it is also about creating new lenses and methods to rethink the culture and the territory we are a part of. By doing so, we hope to not only give marginal cultures another function, but also to re-read them through what we learn in relation to the external input we gain by branching out. We are not there yet — it is quite difficult to do this. We are talking about at least fifty years of history, usually considered through a conservative lens.

To explain more on the idea of branching in and out: I started a radio program Branching In, Branching Out. The Latin word for education, educere, also means to reach out, to branch out. I think this is really what we do. Branching out in the sense of hybridising our understanding of place by reaching out to other ways of thinking and doing that come from places and people beyond our borders. Branching in, both towards ourselves and into the discovery of different experiences and views of Topolò as a location.

For me sometimes it manifests in dreams — I see myself walking in Topolò or in the forest and I discover new places, maybe ruins of previous villages or undiscovered landscapes. I think this speaks so much to this branching in: exploring territories with the desire to encounter something new within what you already know. It still happens in reality too, maybe once a year. The last time was when Dora brought me to a place near the village that she knows well, but where I have never been. It’s a grassy space on the upper side of the village, maybe five minutes walk from my house. What is nice to me is that you not only discover a place that you did not know, but that from there you gain a different perspective on what you already knew.

FL: Did this perhaps happen when people started to come here and explore the village differently?

VR: Not so much, because when people come here for the first time, they look at the place as we did when we first came here too: the mill, the waterfall — things that are typically beautiful. Nowadays, I am touched by small and humble things that people maybe wouldn’t notice upon first glance.

ER: Sometimes I have a feeling of discovery when the season changes, for example. Every season I am surprised — something can be bigger, closer, greener. This, for me, makes a whole new landscape.

DC: My own house was a big discovery! There are quite a lot of houses in this village that are abandoned. You can enter some, have a look. In some others you cannot see anything at all. The one I live in now has no windows approachable from the street. I had never been inside and one day we decided to enter and when I saw the inside I thought: “Yes, this has potential”. I have been living here, slowly adapting and renovating the house for the past five years.

SvA & FL: Can we talk a bit about the evolution of the magazine? Now it is a somewhat serious object that allows you to get in contact with the external world, to bring things back and to reflect on topics related to Topolò. Do you imagine it to change again? Would you like it to become a different tool? Is this enough, or would you like it to shift?

DC: Since the magazine fulfils its purpose at the moment, it could be an interesting time for us to question how to engage locally in a more formal way and start to build upon something that is already here. Maybe we could contribute to the daily newspaper, SMO [a museum about the Slovene minority of the territory] and define our place in this context. This could also happen through writing, curating or through exhibitions that we organise.

VR: Yes, we would like to continue exploring how to bring our way of thinking and doing things into other institutions of the area. We should understand and ask ourselves how to influence the cultural context we are a part of with our methodology of working.

ER: I could imagine approaching more theoretical, commissioned contributors of high regard and including them in our publications as Aljaž did with his interview with Michael Marder in Robida 7: foresta gozd forest.

VR: Yes, that would be nice, but the fact that we are not super selective and that we accept a lot of contributions allows us to be reachable. Everything we did somehow always grew with us. When we were at university, we would reach out to our peers and ask them to contribute. Later we encouraged post-degree students because we were there ourselves. Now, the fact that we desire more depth maybe says something about us. Of course inviting and paying would be a different approach. It would require the management of a totally different budget. Now we have two expenses: print and graphic design, that’s it.

SvA & FL: Have you ever thought about starting other kinds of publications?

VR: If we were to stop the magazine and do something else, I would maybe start with developing books of maybe ten essays, like all the books I have been reading these days. Thinking about change, I am curious to hear from the others how they would see Robida Collective in one year? If they would consider a revolution, what would they do?

DC: I would move to another village and restart from zero all together.

VR: Robida is growing a lot. It’s time for a shift to happen because to continue as we are now is unsustainable.

DC: The momentum we experience at the moment is an intensification of a small and delicate structure.

VR: We are a collective project which has developed through generative, participative friendship. At the moment there is an internal struggle between what it would mean to have time and space for friends, and what it would mean to become a more structured organisation.

I have the perception that Robida is a much bigger group than just the eight of us. This feels a bit rhetorical, but I also perceive visitors and friends that are maybe not super active as part of Robida. Together with the reflections we have with certain visitors, we shape and build what Robida is. I perceive this, let’s say family, as quite large.

To me this is an interesting question I would have for you [Sasha and Francesca] or for all of the people that are somehow involved in Robida: “How much do you feel a part of Robida?” It would be a bit of a problem to me if you would say: “I don’t feel like I belong”.

Something that I would also like to do is to make time and space to take care of possible openings to new relationships that could spring forth from the open call.

SvA: Yes, but how many relationships can you hold?

VR: This is always our struggle: we feel we are mostly working towards organising occasions for others to contribute, meet or engage. We create the structures and others bring the content. Aljaž always says: “I don’t want to do this, I also want to make the content”. It’s an interesting question: do we want to be the infrastructure, the institution or the producers of content?

FL: This bees workshop is something different from what you have done in the recent past. With the Summer School you created a space for other people to encounter while with the bees workshop you made space for something you wanted to learn and then apply as residents of the village. Perhaps here, you made space for yourselves first?

ER: Yes, this is why we kept it small: so we could be focussed and so we could learn what we needed to know in order to start to take care of these 30.000 new inhabitants.

Somehow there is this idea of numbers being of importance and I don’t always understand why. I tend to stress with a lot of people in the same place at the same time. For me, it’s best to do things in small groups, as we just did. It makes it easier for me to organise, to engage in conversation and to give attention and space where it is needed. We could continue to organise intimate moments without them always needing to be with the same group of friends.

DC: The question of numbers is related to how we get funding through organising public programs. Here, doing something that is open to the public is the main way to get public funding.

VR: If we do things like this bee workshop with friends, then what is our destiny? Would we remain small in size? In this case, then it would probably be good for each of us to have interests and jobs outside of Robida collective. On the other hand if we would like to grow, it would be easier to become an institution.

FL: Probably you would like both.

DC: I think the main difference lies in the everyday of being here or not.

–

On Thursday, early in the morning, Vida brought Sasha down by car past Cividale and all the way to Udine so she could catch a train. Francesca stayed for some more days in the area and left with Teo on a late Sunday morning after a long breakfast all together. There is an ongoing sense of feeling welcomed and supported. We will always come back.

A Glossary of the Margins

To define, re-define, invent, ground, re-place. There are words which need a shared definition, an expression; other terms demand new descriptions, neologisms or roots. In their publications and on their website, Robida maintain an ongrowing glossary. This record will be enriched by future temporary and permanent dwellers of Topolove, expanded into a wide assemblage of words for a possible way of dwelling-yet-to-come in post-rural places. The following are definitions that go along with our conversation.

Rurality

Our idea of rurality had to be on the move for several reasons: due to urbanisation, the emigration of people from less developed areas and the desire for a more comfortable life in the city, the phenomenon of empty-ruralities should become one of the modern challenges for progressive learning initiatives all over the world. In Italy, there are as many as 3,644 municipalities, almost half of all Italian municipalities, with less than 2,000 inhabitants, all of which — I am sure — are located in rural areas. These emptied rural areas could present a home for the neglected precarious working class, who find living in the city unbearable, but cannot think of an alternative solution. Proposing an alternative like that needs to offer a specific deconstruction of the term rural itself: the new rurality needs to offer a return into the future, not into the past; it needs to encompass — and not deny — the positive features of a city life and upgrade them with those city-dwellers have long forgotten about: what does dirt taste like, what do different weather conditions do to our bodies, what is it like to come into contact with a snake?

Fear of periphery

The fear of being peripheral, of remaining out, is a feeling and concept that I feel quite strongly while living and working here in Topolove. Working with contemporary culture on the margins in a small village puts you always in relation to the city, to the centre, to which you always look for validation. Fear of periphery speaks about the need to be in contact with urbanity and of the power relations that still exist between culture at the centre and at the margins. This is about claiming power and also about emancipation. It portrays a need to be connected to transformation (which is usually urban). It also reflects what is expected from the periphery (a certain type of work connected to crafts, ancient knowledge or traditions) and how to go beyond these expectations.

Margins

Margins (geographical, topographical, as well as social) as opposed to centres, are spaces which are usually perceived as conservative, slow, un-creative and nostalgic. We like to consider margins as places of “radical openness” (bell hooks), “spaces particularly fertile with possibilities for change” (Catriona Mortimer Sandilands), “zones of unpredictability, at the edges of discursive stability” (Anna Tsing). Margins, as well as peripheries, borders, edges, interstitial spaces and liminal zones are places of meetings, impacts and crossings, where ideas, experiences and cultures collide and intermingle.

Relaxed and disciplined

One of the most prominent Slovene partisan poets Matej Bor once wrote: “The rhythm of Slovene revolutionary poetry must merge into one with our liberation struggle. And what is the rhythm of the awakened Slovenian masses? Relaxed and disciplined at the same time. Why would we search for form in various currents and -isms? Form is dictated to us by our flowing life itself.” Living in an abandoned village throughout the whole year requires intentionality in both discipline and relaxation. While life in the city is guided by the city-flow, in Topolò, the lack of the gaze of another during winter and our consequential habit of this lack turns our gaze to the flow of surrounding nature, our loyal companion: be persistent and disciplined in growing, generous and relaxed in giving.