Mark von Schlegell and Luzie Meyer in conversation with Becket MWN

Pure Fiction is an art, performance, and writing group started in Frankfurt by students of the Städelschule in the eponymous writing seminar taught by Mark von Schlegell. Active since at least 2011, the collective has two publications available from Sternberg Press, and a proverbial iceberg of performances, pamphlets, public readings, and printed matter beneath the waterline. Becket MWN spoke with Mark and founding member Luzie Meyer over a rickety internet connection from their respective locations in the United States, Germany, and the Netherlands. Due to transmission issues, some audio got lost along the way. In the following transcript, the symbol [ ] denotes a gap of a few seconds in the audio, while \/\/\/\/ indicates a scrambled or indecipherable phrase.

Becket MWN: I got really interested in Pure Fiction through two publications, Sibyl’s Mouths [2023] and Hamlet, mise-en-scène [2014]. I wanted to start out by asking you what were the origins of Pure Fiction? Would you call it an imprint or a publishing collective?

Mark von Schlegell: It can be both of those things, but it is a loose title signifying a group of people. It began as a seminar called Pure Fiction at Städelschule, and Luzie was in the first class we ever did. [ ] It was a writing class at an art school, so we were involved in doing lots of publications, performances, crossing the line between writing and art. And then we were asked to do events and performances and readings and publications outside of the school context. So when the school saw fit to discontinue the seminar, we just kept it going as a collective.

Luzie Meyer: The seminar was always dependent on student initiative, because it was an addition to the school started by students who got Mark to come to the school, and then continued to take initiative to make it possible for Mark to stay. And the group or collective is still a shifting constellation based on initiative, I would say. Whenever someone has an idea, like: “Let’s take part in this book fair!” or “I got this invitation”. It lives from individual engagement and opportunity and initiative.

MvS: There’s no precise definition for what it is. It’s very loose, spontaneous. [ ] Because we’re never exactly a writing collective or a performance collective or a seminar, the hybrid quality becomes central.

BM: Was the class originally organised around any particular genre or topic, or was it a more open engagement with art and writing?

MvS: I have a literary background, so as a teacher I always felt what I could transfer best is literature, because I have a PhD in English, so we always organised around literary, classical texts like Don Quixote, Moby Dick, Shakespeare, or Virginia Woolf, this canonical stuff.

LM: And also kind of take them apart, because the group was quite open. Whenever there was a critique or addition to this canonical basis, it became integrated, so the discussion lived from this heterogeneity of [ ] perspectives and approaches. I don’t know how we started to do the performances; I guess we had readings at the beginning, and then there was the Hamlet thing.

MvS: We were invited to do a large-scale performance of our own choosing at Portikus early on. And so we decided to do Hamlet silent, with a version of the script that one of the students, Clementine Coupau, came up with. A version of the play with only the stage directions. So the success and amazing discovery of that project opened up Pure Fiction as a special entity of its own, because it turned into a large production with sets and costumes and music and lighting, and we didn’t know it would be that, and suddenly the students sort of self-organised. Overnight it was this organisation!

LM: We had a lot of support from the curators at Portikus, under direction of Sophie von Ophers, because it was part of this Jack Smith festival [EXTRA TROUBLE–Jack Smith in Frankfurt, 2012]. Because there was money for this, they invited Susan Cianciolo from New York to do the costumes. Some people got really involved with the make-up, others did props, and some of us did more like dramaturgy and writing and things like that.

BM: It seems from the publication like there were a lot of multiple roles people played.

MvS: Yeah it was a process of discovery. The roles just came out of people, like it was inside of them already and they hadn’t known, it was almost this unconscious ur-theatre. Some of the students had really been trained in theatre, so they could teach other people how to fence and stuff like that, but it was pretty wild how we discovered suddenly, “Oh, I want to do exactly this.” Everybody fell into place.

LM: Or everybody looked for their place. The openness, this non-definition of what it will become or what it is or what it is supposed to be, opened up a lot of space for people to think about how to integrate whatever they could do. For example we did another one in [Kunsthalle] Darmstadt [The Tempest Project, 2017].

MvS: Der Tempest.

LM: Ellen Yeon Kim wrote the screenplay, or rewrote The Tempest, with other parts of Shakespeare plays, and made it more of a feminist, anti-psychiatric revenge tale, and I did the music for that because I was working a lot with electronic music at the time. So everyone had the opportunity to go like, “Oh I could do that!”

MvS: And you were in it, you didn’t just do music.

LM: I was also singing, or like a voice actor.

MvS: We always invented new ways, because none of us are trained actors, and none of us were really gonna memorise all the lines in this situation, so we figured out new ways, or perhaps old ways. We would have one person reading the lines while another person performs the body of that character; in Romeo and Juliet, for instance, we had a chorus of all the voices, it was quite interesting.

LM: \/\/\/\/ in a corner or whatever [on a raised scaffolding stage], and they were reading the script, and then there was the performance going on, so it was kind of a live narration, or live reading.

BM: I love the book that came out of Hamlet, mise-en-scène, and so I was curious how the live performance translated into the publication. There’s a lot of beautiful material from Jack Smith, stills from his Hamlet in the Rented World (A Fragment) [1970–1973], and some scripts he wrote on this General Electric stationary, so I was curious how the book came together.

MvS: Well the book, in certain elements the designer Brian Mann did a great job; but all the images of the faces that are in the book came from a film. What we did was document the production by ourselves while it was going, so if one person, say Olga Pedan, was Hamlet, another person, Collin Witaker’s role was film-maker. Colin just made a film the whole time we rehearsed and performed, and that was his job throughout.

LM: I think I remember he used actual film because that was what he was going to do in the school film workshop anyway, and he brought it into the play and made this Hamlet film that was then digitised, and someone else then edited it.

MvS: He did close-ups of every character as part of his film so at some point you’d have to go sit down in front of his camera for a few minutes, almost like a Warhol Screen Test. And so all of those pictures of close-ups are from his film. We gave Julien Nguyen the manuscript and he drew these insects onto random pages as a kind of adornment/mutilation. We tried to do it our own way in every element. But the thing that was the real surprise was how it looks like a magazine. That was the designer, Brian; to be honest, Michael Krebber and I were a bit worried about the publication when we saw the PDF. We thought it was too perfect, and professional-looking. But when it was printed like that, we thought, “Oh my god, this is the greatest magazine ever!” The physical production somehow changed everything, it made it so light. So we learned a lesson there, to experiment in every element.

We were really lucky to get that essay by Juliane Rebentisch: “Camp Materialism”. When we got that early on, we were really excited. That was really important, so the book wouldn’t be just us talking to ourselves the whole time, in Jack Smith’s face.

BM: Jack Smith is an important figure of camp cinema and film-making, and I like this idea of his that comes up in the book called Reptilian acting technique. At some point it’s defined as “Let’s not pretend”: instead of “Being-as-Performing-a-Role”, as Susan Sontag put it in Notes on Camp, it’s like Performing-a-Role-as-Being, an inverted version of camp.

MvS: One element of that technique that we really impressed on everyone, was that while you’re performing every actor should pick one person in the audience and direct their entire performance towards them secretly.

LM: And it was also non-verbal. You were supposed to recite the text in your head to channel [ ] I don’t recall in detail anymore what the philosophical or practical idea was, but it was about embodiment of an intensity that built up inside of you, and that would “inevitably” show.

MvS: In particular Olga who played Hamlet, she really memorised all the soliloquies, and when she stood there not speaking them, she thought them. [ ] And then every actor could pick one line from the play and speak that one line, so everyone could say one sentence of their choosing from that character.

LM: I played Horatio, so I had the last word: “All this I can truly deliver.” I was sort of the master of ceremonies.

MvS: What a cool line, it’s like he’s a journalist; he is the writer in the play.

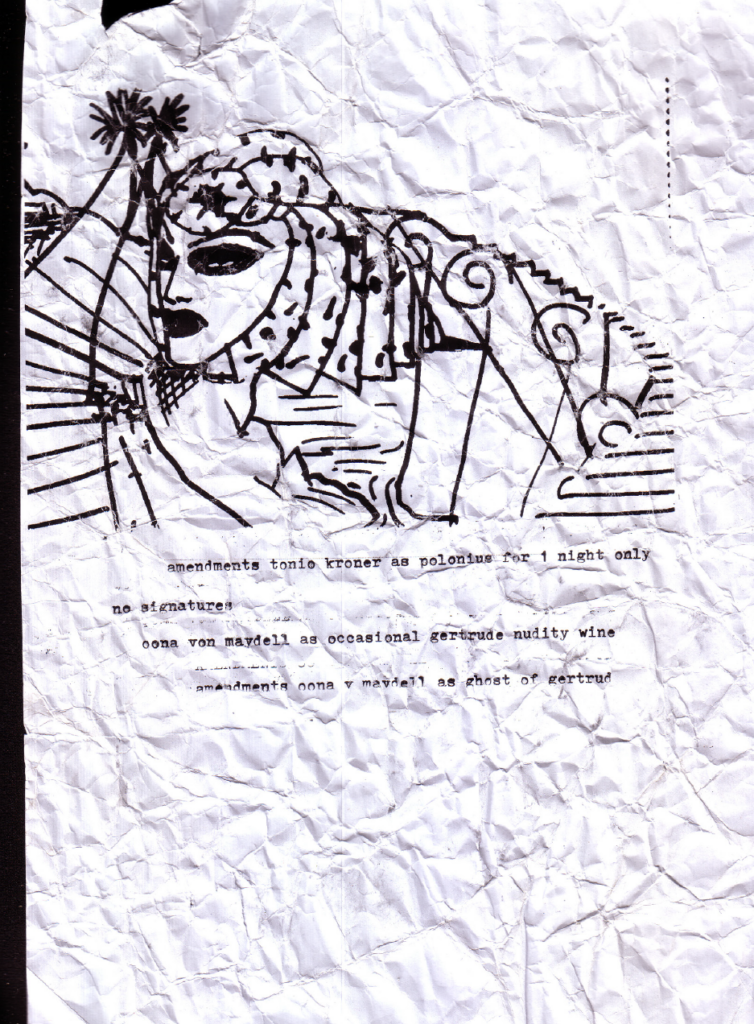

LM: The framing character; Ais [Aislinn McNamara] and I were also live typing during the performance on a typewriter. We were typing on it during the performance, and crumpling up the paper and throwing it into the audience and onto the stage.

MvS: They were poems, and they were really amazing. I think I only have one original somewhere.

LM: I have a couple in my studio, and one of them says “the queen, squatting over a mirror, looking at her bumhole”.

MvS: Someone in the audience just gets that from the sky because they were high above everyone typing the whole time. That was the key part of our ideas for keeping the writing seminar going. Even though we are doing all this art stuff, it was important that we were generating text all the time, shedding poems.

LM: The live typing remained, [ ] also during performances when people were writing their own texts, we had people live typing and taking minutes, and whoever was typing was writing on the spot, their own writing but also incidentally including bits and pieces of what was said.

MvS: Yeah, imaginative minutes.

We tried to involve technology too even though we were very literary you know. In one of them we used the drone. I think it was the first time I ever saw a drone in any kind of performance, in Romeo and Juliet, and it landed in your [Luzie’s] hair — by chance.

LM: And we used projectors a lot in exhibitions and also during performances. There is this computer program that you can just feed a text and it shows you the text word by word.

MvS: It just flashes one word at a time. You can go really fast, so we wrote poems for that. We had one really interesting reading and installation, I think it was one of the most amazing things I ever saw. We installed in the baggage claim [at Frankfurt Airport] on the TV screens! I don’t know how they gave us this freedom. So while people are waiting for their baggage, these strange intense punk poems are coming up on the screen. And we did a reading at an airport bar.

LM: You could hear the reading all over the airport. It was on the speakers on the landing strip, and the hallways, I think.

BM: It feels like the performances are a central part of the activities of Pure Fiction.

MvS: Yeah, we ended up doing a splinter performance group called Impure Fiction sometimes; we did Molière, Brecht, three Shakespeare plays, various other self-written items.. But also all that time we were publishing. We published numerous zines and pamphlets and books. That was always part of Pure Fiction, insisting on publishing.

LM: And the material that we produced in class and also after outside the school context, it was always super heterogeneous, at first we were supposed to write short stories only, but somehow this didn’t —

MvS: — immediately, I said no poetry, and immediately poetry was all we got.

LM: I think that especially [ ] that this seminar happened at this school, because otherwise I think writing would not have become such an important part of my own art practice, and it made me, maybe that’s too cheesy to say, but it really gave me a structure for my artwork, or it’s the central framework that helped me find my practice and put it together and make it make sense [ ] the writing became sort of the grounding element. And without this seminar I would probably never have discovered this.

MvS: We discovered together how important writing is to any kind of art now. Whatever strategies you’re taking as an artist, there’s always a place for writing to be a part of that. But I remember Luzie, as a reader and writer that you were a big part of the class and sort of helped flavour its imagination; but your writing, I think you were trying to do what I asked, and then one day I remember when you wrote and read aloud this long poem, do you remember that? I felt like, Wow, that’s her voice all of a sudden.

LM: \/\/\/\/ Bread and Butter!

MvS: Yeah that was really spine tingling, it was so different and so clear.

BM: I think the role of writing in art programs is really interesting. When I was doing my MFA, we had a day when we shared pieces of our written thesis. I went to a small program, and we had gone through many crits together over the two years we were there, and I think we were pretty used to sharing our work with each other; but then suddenly with text there was this feeling of being naked, and sharing something that none of us had thought of as our medium, and expressing things that were very meaningful or important to us without the filter of any kind of stratagem or installation technique. It was very naïve somehow, and very vulnerable.

LM: Yeah it’s vulnerable and there’s such beauty to it if you read texts together that you’ve produced on your own. It’s also incredible, the multiplicity of voices that you get to experience in those situations. Everyone really brings something very unique.

MvS: But also maybe there’s a mutual influence going on too. There was also this funny similarity between people’s writings. We created a genre we called “Tropical Emo” because everyone was writing about fancy islands and depressed people. It was really weird!

LM: There was also a sort of melancholic dandyism, that was also a branch.

MvS: That’s why it was kind of exciting especially at first there; at a lot of art schools in Germany people work in one class, someone is in so-and-so’s class and someone else is in another class, and they rarely interact in terms of their work. And suddenly everyone’s in this seminar together putting this kind of naked stuff with no agenda. There’s no posing going on here; it’s pretty raw. [ ] And then someone once described it — I always say this, it gets a bit old — it was like social bungee jumping. It was so exciting for the students to interact at all in that context. I didn’t realise that at first, but it was just exciting for people to be there.

LM: Yeah, in the beginning I remember it was totally nerve wracking [ ] For me at the beginning I couldn’t write, I think it took me like five classes and Mark kept saying “Why aren’t you writing? You’re always here; you have to bring something for the next class.” And he kind of made me do it, and I wrote my first short story, which was about some sort of bog with fires.

MvS: The thing I just loved so much was the way [ ] some local restaurant or bar would invite us to do a reading; I really loved the way we interacted with the public.

LM: Yeah, and the group still does it. After school it was [The Tempest Project at] Kunsthalle Darmstadt, then it was KW [Institute for Contemporary Art] here in Berlin, where we did Miss St’s Hieroglyphic Suffering [2018], which was sort of a response to an Ariana Reines script [Telephone], there was also an iteration of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle at Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover.

BM: Maybe we could talk a bit about Sibyl’s Mouths. I’ve been reading the book over the past few weeks, so I’d love to hear about how that project started out. What was the beginning point, and how did it develop from there?

LM: Well, there was an exhibition project that preceded it, and that was born in Mark’s head. There was this idea of Pure Fiction, “Shifting Theatre” and different media formats.

MvS: It was during Covid, so you couldn’t really do performance normally, so how can we shift the idea of performance into an exhibition format. First we did this exhibition called Shifting Theatre: Sibyl’s Mouths, but we decided the idea together once I proposed that we do a project with this at the Kölnischer Kunstverein.

LM: I think Rosa [Aiello] brought up the book, the Mary Shelley book.

MvS: Yeah, in class we would all read one text together, so she proposed, since it was relevant to Covid times, The Last Man by Mary Shelley. So we all read that book before we conceived our projects.

LM: The framework of this book is about finding these oak leaves, I don’t remember who —

MvS: Mary Shelley herself finds them herself in the introduction —

LM: She finds these oak leaves in the cave of the Sibyl near Naples, and on these oak leaves there are prophecies, written in many many different languages and in different lettering, and these prophecies on these leaves are supposedly the story that you’re reading.

So the idea for the exhibition was that of many mouths, and some of those things also came into the publication, as if it were a gathering of prophecies from many mouths, or in many different voices. For me, the idea of the Sibyl and the cliché of the many mouths was super interesting, or being a mouth or an agent of God. That was one of the ideas, but also the time that you have in prophecy, the future-perfect tense or something like that —

MvS: She’s in the future reading the past. It’s an ancient cave, but it’s a future text. Well I think writing has a relation to time that’s like that — it’s in it but out of it.

LM: Because it’s something that you do in the present, but it also is fed from memories and projections.

MvS: And it’s printed years later, and looked at by people in the future looking at the past. It’s all just so odd.

BM: On the idea of time, I really appreciate your contribution to the publication, Mark, “Her Stories of the Revival”. It has all the time stamps in it of a recorded archival document, but then it’s also history or archive as a hypertext, because there are multiple timelines that are being archived at the same time. Even within the piece, there is a physical document to which the recording transcript refers, so there’s an inter-archival textuality there. So it really has this future-past orientation.

MvS: It’s a tricky text to publish, so here was my chance to publish this text correctly. One page is a scan of a letter with the colour of the page, and all these things you never really see in a book; but our publication gave us a chance to do this, so I was thinking in terms of how to use the power of publishing from the writer’s perspective with that piece. Writing as we’re saying is time travel, so it’s fun to reveal publishing’s role in all that too.

BM: Luzie, what I appreciate about your contribution in the volume, “Am I a Mouth or Am I a Voice?”, is how much it reads like a score; it makes the voice visual and material, there’s different instruments and sounds that are indicated by certain punctuation and ciphers. I was really interested in the aspect of ventriloquism, which is also what this text thinks about in terms of the Sibyl.

LM: I liked the idea of putting a score in. It has this idea of live [ ] embedded in it. It’s also interesting for me how we approach older documents, because we don’t know how they were read or who read them aloud in which context, or what the situation was in which they were performed. I performed this text once at a reading here in Berlin [“Amatter” at Cittipunkt, curated by Sanna Helena Berger and Adrienne Herr]. I had several percussion instruments and I handed them to members of the audience, who could follow the score and play their instruments whenever it was their turn. So there was a pattern or rhythm created. \/\/\/\/

I make these sound poems, where I have rhythms and sounds emphasising parts, or [ ] going against the writing, and direct the attention of the reading. So that’s what happened live there in the space, and the score is now my contribution to the book, as a historical trace of a performance, so to say.

MvS: In the exhibition of Sibyl’s Mouths, Luzie made puppets, so ventriloquism is related to those too, in a way. She made puppets of all of us, the people in Pure Fiction at the time.

BM: What was the editorial process of the book? Some of the contributions are from the core collective, for example “From the Hand”, a beautiful cycle of poems by Erika Landström; but there is also an Annie Ernaux text, a piece by Amelia Groom, and some others from outside the collective, so what was that process?

LM: We met a couple of times; sometimes not all of us were there in the editorial meetings, because we worked from different cities at the time. I guess we wanted to both have it be part of the Pure Fiction tradition, but also be more independent from the school context, and open the project up to a broader scene of writers and artists. So everyone had ideas for possible contributors. Erika [Landström], for example, brought in writers she knew from living in New York. We asked ourselves “who would be interesting to publish in this context and who do we know whose work relates to the themes of the book in a broader way,” and we intentionally tried to make it a diverse and eclectic publication.

MvS: It’s a bit of an anthology of art writing, I would say. Some of the people, maybe not Annie Ernaux, are in the art context in some way, either critically or artistically, people who are writing on the side all the time, but maybe you know them doing other things usually.

LM: Many of them are artists, but not all of them.

MvS: Because there is this genre, “art writing”; I mean, nobody really knows what it is, it’s not art criticism, it’s artist’s writing. You see a lot [ ] But with Annie Ernaux, this was before she won the Nobel Prize, and Rosa just wrote her out of the blue, and she said yes, I love this idea.

BM: Is there anything you would want to highlight about the book?

MvS: Well, one thing I like about it is that just flipping through it you see so many different languages. It’s not just in English; you see a global, poly-linguistic vibe in it.

LM: I would just encourage everyone to have a look at the variety of voices.

MvS: And styles; there’s poetry, there’s scripts, there’s stories, essays, but they all sort of link together in nice ways without overdoing their difference or relationship.

BM: It looks like such a design challenge because there are so many different ways of dealing with the printed page. Not only the multiple languages, but drawings, photographs, text that’s cut out of magazines and pasted together.

LM: It was definitely a design challenge, and I think you can’t say enough how great a job Ellen [Yeon Kim] did bringing that all together. She really did a lot of work. That was the most difficult part of working in a group, because there is no centralised way of working. It’s just very uneconomic somehow to work in a group, where people’s minds just function differently and everyone has their own priorities and ideas, but in a good way as well. You get to know the other people very well, you have conflicts about certain things; I learned a lot of communication skills.

MvS: I’ve talked to people who’ve been in collectives and they’re like, “The secret is, that one person really has to run everything”. But in our collective, it really isn’t that way. Really nobody runs it. It has its own life as a result. When I see the book, I’m like “Wow, that’s so odd”, because nobody actually conceived, ever, that it would look like that or be that. It came of its own with us; it’s like a ouija board, where everyone’s touching it, it spells out this message that nobody actually intended it to say, but it’s there, and we want it there and we helped it come out. I really enjoyed that. Because there’s no overall single person saying, “This is the concept here”, the designer needs to really make it come together.

LM: I think that Ellen did such a good job because she tried to integrate our ideas. She gave us space to comment and then she integrated it and didn’t get lost in it. The book looks like a complete book, and it is a complete book, which is amazing considering how it came about.

MvS: We have strategies as Pure Fiction. For our visuals, we often go to Aislinn [McNamara] to do posters and covers. She loves doing text art, so she did the cover drawings and some of the drawings inside too. We just knew to ask her, that’s our tradition. But in the end we decided to preserve this quality we’re discussing now, by not pretending that there was this total knowledge of what the book would turn into. Then it’s less of a Sibyl’s mouth anyway, it’s more of an editor’s mouth.

LM: Yea it’s true. I think now, without an introduction, the book really provokes more of an encounter, like finding those leaves in the cave.

Luzie Meyer (*1990, Tübingen // www.luziemeyer.net) is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and translator. She studied Philosophy at the Goethe-University and Fine Arts at the Städelschule in Frankfurt. Meyer’s texts are worked into exhibition settings as videos, sound pieces, performances or installations. By suffusing institutionalized habits of meaning-making with aesthetic breaks, semantic entanglements, or alienating effects, Meyer opens up new possibilities of expression and signification. Through musicality, absurdity and intertwinement of various genres, she designs countermodels to patriarchal grammars. Meyer’s work was shown recently at Kunsthalle Bremerhaven GER (2022); Istituto Svizzero in Rome, ITA (2022); Sweetwater Gallery Berlin, GER (2022); MINT in Stockholm; Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, GER (2022), Fanta Milan, IT (2021). Meyer taught at the KH Weißensee art school in Berlin between 2019 and 2021, in the framework of a pre-doctoral fellowship. Her writings were published in Texte zur Kunst and Conceptual Fine Arts, in Edit Magazine #84/85, Starship Magazine #17, Agathe Bauer #ZERO and on www.c0da.org. Meyer is also the co-editor of the compendium “Sybil’s Mouths – A Pure Fiction Publication”, published by Sternberg Press in January 2023. Meyer is a long-term member of Pure Fiction and has been part of the Matter in Flux group since 2023.

Mark von Schlegell earned a Ph. D. in literature from NYU in 2000, and directed the Pure Fiction Seminar at Frankfurt’s Staedelschule from 2011-2018. His first novel, Venusia (Semiotext(e), 2005), was honor’s-listed for the Otherwise Prize in science fiction. He has published more than eleven books and numerous stories, scripts, essays, and experimental short form writings, and continues to write, perform and collaborate with independent artists in experimental projects around the world.

Becket MWN is a writer and artist based in Amsterdam, NL and originally from the United States. He received his MFA from the University of Southern California in 2014, and was a resident at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in 2016-2018. His recent projects have focused on the relation between language and the production of the self, and the relation of media to forms of contemporary life. His most recent text and performance, commissioned by the Inter Media Art Institute (Dusseldorf, DE), used the film editing technique of “twinning” as a model for the virtualization of much social interaction and new, posthuman concepts of subjectivity. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions include The Tail (Brussels, BE), Kevin Space (Vienna, AT), Kunstverein Graz (Graz, AT). Recent group exhibitions include Shimmer (Rotterdam, NL), Rongwrong (Amsterdam, NL), Kunsthalle Fribourg (Fribourg, CH), Kristina Kite Gallery (Los Angeles, US), and Vleeshal (Middelburg, NL). He also publishes art criticism and essays under the name Becket Flannery.