Todd Stewart & Robert Bailey: The Course of Water

The Course of Water – Fieldnotes from California’s Owens Valley explores the environmental and social histories of California’s Owens Valley by attending to the implications of its peculiar hydrology. A stolen river, a dry lake kept wet, Sierra snowmelt, turquoise springs: water takes strange paths in this desert landscape, rerouted by the lives of the people – Indigenous, settler, internee – who have called it home.

At the turn of the twentieth century, a lack of water resources threatened to stall the growth of Los Angeles. The city began diverting water from the Owens River – over 200 miles away – culminating in the construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913. This led to the eventual desiccation of Owens Lake and much of the surrounding valley. To date, Los Angeles has spent billions of dollars mitigating carcinogenic dust by transforming the dry lakebed into a wetland.

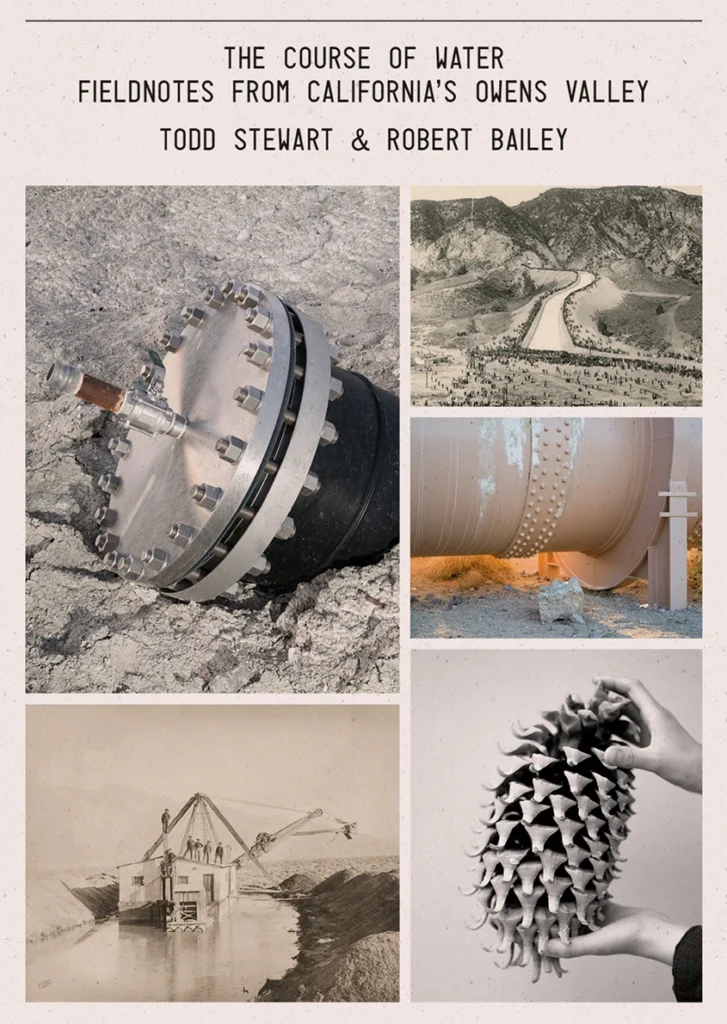

To represent the allusive richness of natural and human flows in the Owens Valley, Todd Stewart (US) pairs his photographs of the region with select archival images, creating a complex visual map that the writing and notes of Robert Bailey (US) further deepen. What emerges is an occasion for viewers and readers to navigate thematic currents that intersect like the natural and artificial channels of this singular watershed.

Stewart’s photographs depict this human-made landscape and its sustaining infrastructure as a dizzying knot of connected waterways. Other images touch on the contested meaning of water in the valley: a stark presentation of an Eastern Mono water basket; orchards planted by Japanese people interned during World War II. In the background, the region becomes a stage – movie stars shooting in the nearby Alabama Hills and Édouard Manet depicting their namesake, the Confederate ship Alabama, sinking during the United States’ first Civil War.

The Course of Water offers evidence of how greed and hubris affect the planet and people, trapping the essence of life within controlled channels. Here, a looping water cycle appears: precipitation runs down from Mount Whitney, disappears below ground, reemerges a thousand years later in a hot spring, forms the Owens River, and disappears into pipes that help make Los Angeles possible. Archival images nuance this story, from the settler enablers of the valley’s transformation to the paths of Indigenous irrigation ditches. Drawing on these materials, Bailey shows how colonial patterns persist in current remediation efforts, even as Indigenous gardening resists in an austere climate made harsher with every sip the metropolis takes. If water is life, then The Course of Water shows what happens when life is deferred.